The Information Blocking Rule: What do Healthcare Providers Need to Know?

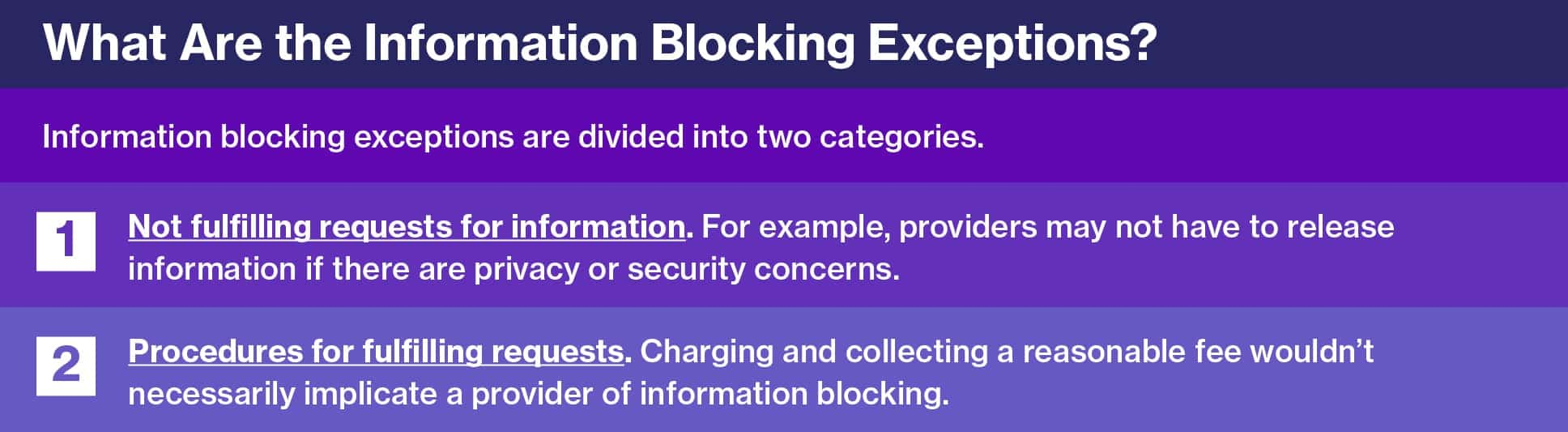

On October 6, 2022, new rules on information blocking established by the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) took effect. Here’s what all providers need to know about information blocking, how it’s defined, who the rule applies to, and steps that need to be taken to remain in compliance.

What is Information Blocking?

Information blocking is defined as a practice that “interferes with, prevents, or materially discourages access, exchange, or use of electronic health information, and is known to be ‘unreasonable’ by a provider.” The Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) believes information blocking “poses a threat to patient safety and undermines efforts by providers, payers, and others to make the health system more efficient and effective.” Consider a provider policy that requires patient consent before sharing medical information with a treating provider. This practice could interfere with the exchange of information, be considered information blocking, and result in negative patient outcomes.

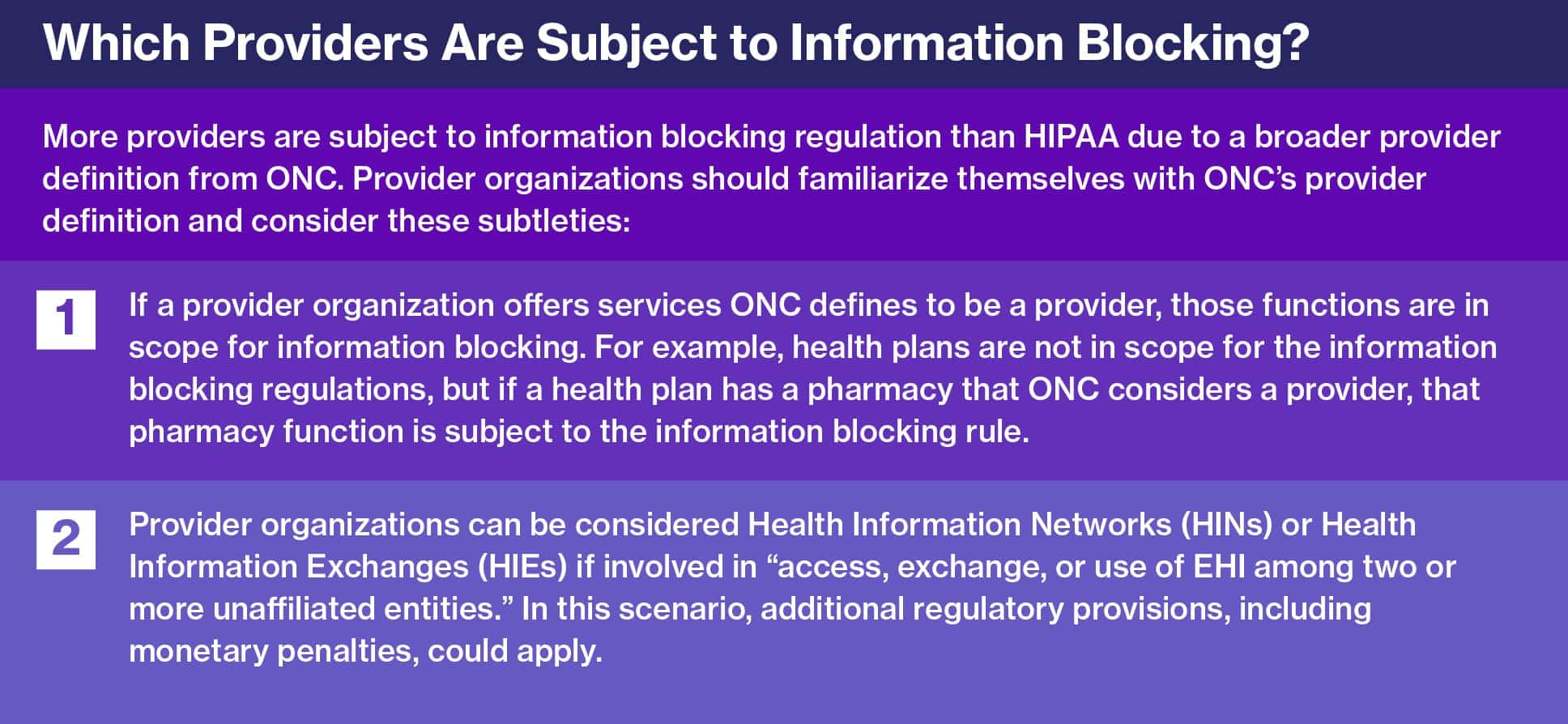

To address information sharing challenges, a bipartisan Congress legislated improved availability to access health information by prohibiting information blocking through the 21st Century Cures Act. As of October 6, 2022, compliance with ONC information blocking regulations was required of providers. Rulemaking on provider disincentives for violations was recently released by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

How Does Information Blocking Relate to HIPAA?

Information blocking builds on HIPAA’s privacy and right of access regulations from its aligned goals to borrowed definitions. While the regulations are complementary, in some cases, the regulations require a paradigm shift in thinking. This article highlights the differences between HIPAA‘s information access requirements and the information blocking rule to help position provider organizations for compliance.

When Does Information Need to be Shared?

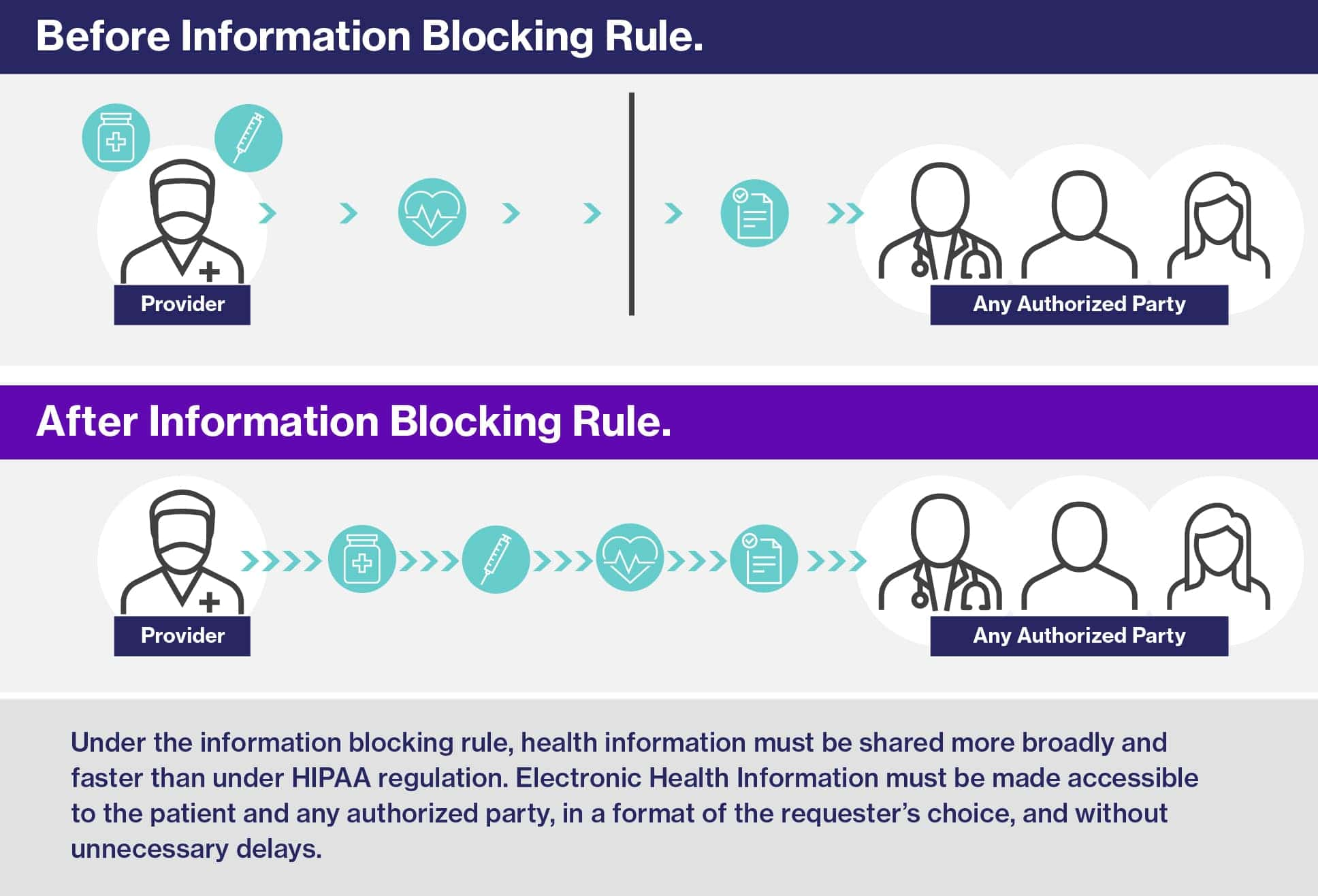

The information blocking rule mandates that providers share data unless specific conditions called exceptions are met. This is a fundamental change compared to HIPAA, which states the conditions under which it is permissible to share data but does not mandate sharing. For example, under HIPAA, a treating doctor is permitted but not necessarily required to provide patient records to the patient’s Primary Care Physician (PCP). But, under the information blocking rule, the treating doctor’s records must be accessible to the patient’s PCP. This mandate to share information applies to providers and any HIPAA authorized party, including patients, their representatives, external providers, authorized 3rd parties, and public health authorities.

How Fast Must Information be Shared?

The rule requires sharing information faster than HIPAA, where providers were allowed up to 30 days to respond to information requests. In contrast, the information blocking rule aims to prevent delays in releasing information unless “necessary.” Although the “necessary” standard introduced by information blocking regulations remains open to interpretation, ONC provides examples of practices likely not considered “necessary.” Delaying the availability of data on provider portals, or policies that block the release of patient test results, unless physician-reviewed, would likely not be “necessary” and could be information blocking. In general, providers should be looking for ways to share information as quickly as possible and should no longer assume they have 30 days available to respond.

What Data Needs to be Shared?

HIPAA and the information blocking rule impact nearly the same patient data. ONC’s information blocking rule requires sharing electronic health information (EHI) in a patient’s designated record set (DRS). The DRS is a HIPAA concept and includes medical records, billing records, and records used to make decisions. These definitions were aligned intentionally and resulted in the rules covering nearly the same information. Despite this alignment, content in a DRS can vary. One reason is providers often create or maintain different information while delivering patient care. Additionally, the “used to make decisions” language is subjective, and interpretations vary. With a renewed emphasis on DRS sharing coming from information blocking, an up-to-date DRS policy and a firm understanding of the DRS and EHI concepts help position providers for information blocking compliance.

What Data Format is Acceptable?

HIPAA simply requires fulfilling data requests in a readable hard copy format or another format as agreed. However, the rule establishes the need to provide content in the format of the requester’s choice. This could be physical media, electronic access, or in new machine-readable formats introduced by the new regulations. Only offering images on outdated media types like CD-ROM / DVD, or denying requests in a specific format could be considered information blocking. Providers should look to implement improved data access and sharing capabilities offered by Health IT vendors in support of information blocking regulations.

What are the Information Blocking Exceptions?

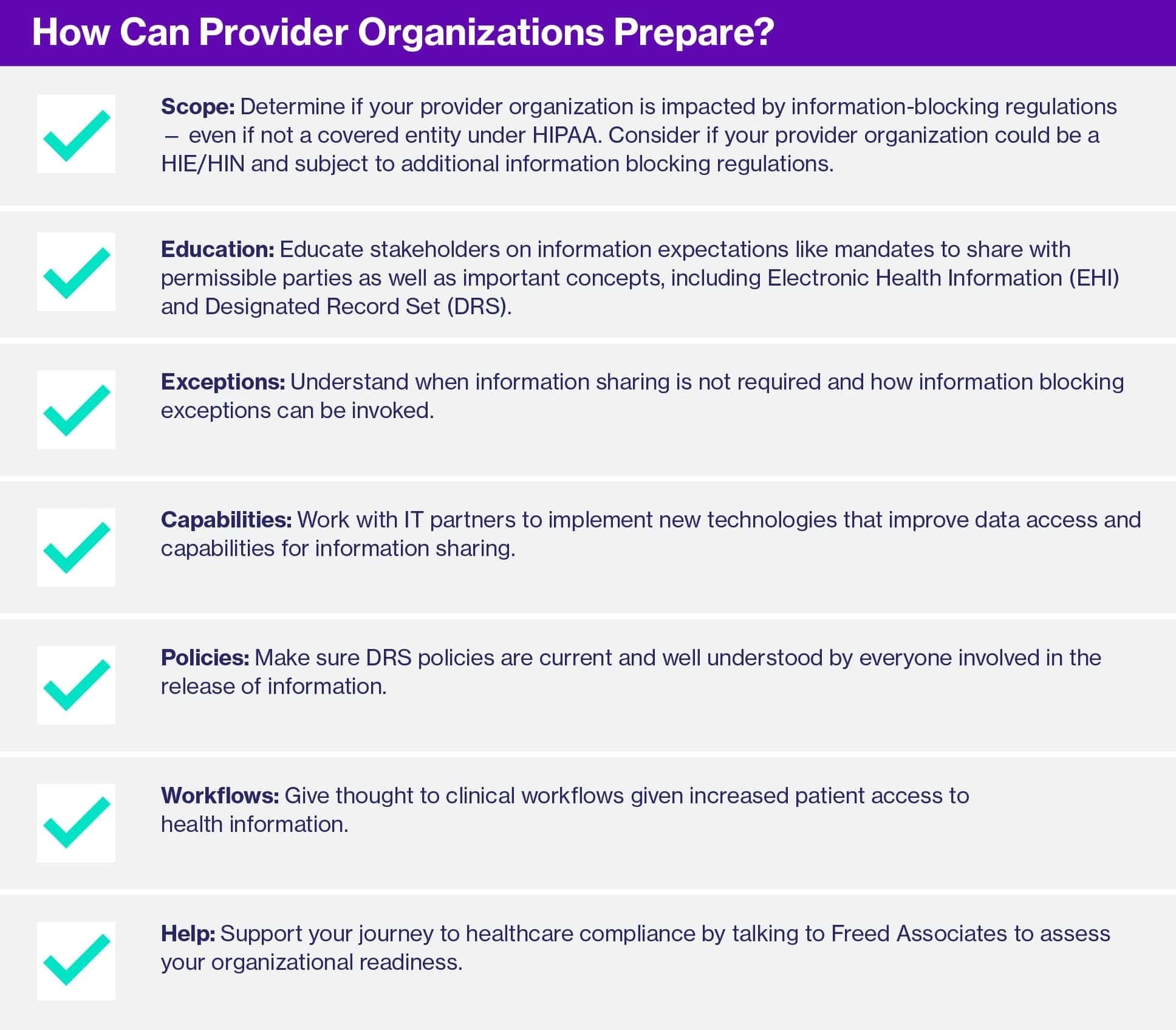

Providers don’t necessarily have to release all information that is requested. ONC defined eight information blocking exceptions that offer providers “certainty that, when their practices meet the conditions,” it “will not be considered information blocking.”

In addition to the allowed exceptions, providers do not have to release information when it would violate state or federal laws.

How is Information Blocking Impacting Patient Care?

Providers should be mindful that patients are getting more complete and more immediate access to health information than ever before. These changes can result in increased patient engagement with medical records. Patients can see test results before a provider reviews results. Provider notes are available and can be viewed shortly after, or even sometimes during a doctor’s visit. Companies that specialize in health information aggregation are able to offer capabilities that the provider may not be able to match, including integrating patient data from multiple sources. This improved access to medical information can impact provider interactions and have clinical workflow considerations.